During a recent presentation and book signing, one of the audience observed that wherever I have been the trappers and mountain men were there before me. On the surface, it seems like a reasonable statement. On further inspection though, why indeed would they have been in the higher elevations during the winter?

The mountain men of the early 19th century on the most part did not come west just to see what was out here. Before the Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery Expedition left St. Louis in 1804, the British and French were already divulging information about the bountiful fur harvest ready for the taking. In 1806, the Expedition was coming down the Missouri River after having been gone for over two years when they encountered two trappers headed upstream in what is now North Dakota.

A short time later, a member of the Corps of Discovery John Colter, given an early honorable discharge, headed back upstream and briefly joined these men. In 1807, he went to work for an American fur trading company as an explorer, or scout. After visiting one area, he came back with a report of seeing bubbling mud pots, boiling pools of water, and steaming geysers. Met with derision, his discovery was dubbed “Colter’s Hell”. Some 65 years later the area would become the world’s first national park and named Yellowstone National Park.

Most mountain men were “company men”, that is, they worked for a fur trading company. Their job was to trap not explore. From 1810 to the late 1830s, approximately 3000 men trapped furs in an area 200 miles south of the present day Montana and Canadian border down to present-day New Mexico. The explorers for these fur-trapping companies, for the most part, did their scouting during the summer.

In short, most mountain men were motivated not to summit peaks or bust through an impenetrable area during the winter, just to say they did it, but to make money off the fur trade. If an explorer did summit a peak, it was generally to survey the surrounding area.

My winter routes typically take me into the high alpine regions where I stay as much as possible. There are few animals and birds up there. Deer, elk, and the American bison, more popularly known as the buffalo, are in the lower elevation winter ranges where they can forage through the winter. For similar reasons, beaver and muskrat need streams and forests, none of which exists in the alpine regions. The carnivores follow their food supply into the lower elevations. For that same reason, the mountain men stayed in the lower elevations, following their fur supply.

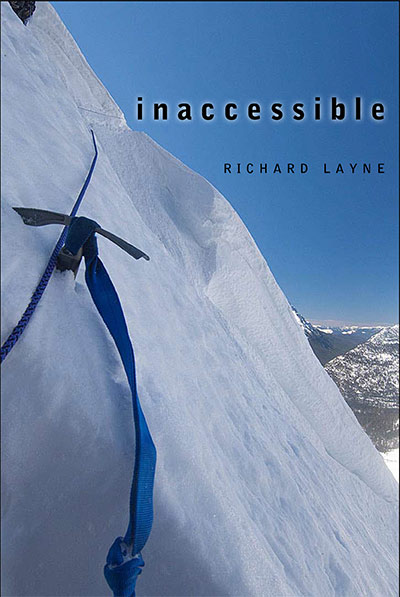

There are also noteworthy differences in the equipment they used compared to the gear in my inventory that made travel into the high country more difficult, if not outright impossible. With their equipment, they could do things that I could never do with my gear. There is no way I could build a cabin, kill an animal for meat and/or for its hide. On the other hand, the mountain men’s equipment was useless in aiding them to climb or traverse 60° to 80° snow and ice slopes. None of them carried crampons, since the first crampon design was in 1908. While the ice ax existed, it was still in Europe.

What the mountain men sought required them to use numerous horses and mules to carry their supplies and equipment. Like a human being, stock are unable to move in deep powder and snowpack, much less forage for their food. Just to preserve their essential stock required the mountain men to stay where their animals could forage through the winter.

Like the mountain men, most of my travel is with snowshoes. That’s where the similarities pretty much come to a halt though. Their high maintenance and heavier flotation devices were made of wood and leather thong manufacture, while mine are aluminum and polypropylene construction. Additionally, my snowshoes have steel alloy teeth to grip in a snow crust, making them far superior in the steep ascents and descents of the Rocky Mountains. Even with the teeth of the snowshoes I possess however, the flotation devices cease functioning in the steeper angled peaks of the Rockies. That is where the mountaineering gear is essential. Without the technical gear I possess, that did not exist during the days of the mountain men, any attempt to access an area like Hole in the Wall in Glacier National Park would have been a suicidal failure.

For the 462-mile winter trek in 2015, I have 599 pounds of food and fuel. Of that, 135 pounds is fuel while the remainder is dehydrated food and olive oil. I have 34 resupplies along a one-way route and carry a 4-pound tent. In a similar manner, the mountain men had trap lines and log shelters containing supplies scattered up and down those lines. Their food was similar in some respects such as pemmican, dried meat, and flour. Unlike me though, they ate huge quantities of fresh meat, while most of my food is vegetarian. Without that fresh meat, in September 1805 the Corps of Discovery almost starved to death getting across the spine of the Bitterroot Range and ended up dining on horsemeat.

Something else that has happened are the monumental changes that have taken place with the equipment in the last 200 years. While my crampons and the teeth on the snowshoes are steel, everything else is lightweight aluminum. With the exception of the wool socks and some goose down, everything I wear is synthetic material. In short, the load I carry today is probably more than 50% lighter than 100 years ago. That means I can carry more supplies for longer winter trips, and into areas that would have been untouchable a century earlier, much less 200 years ago.

My winter bedroom weighs 10.25 pounds, which includes the accessory chair and a three-quarter length self-inflating pad to go with the chair. My bedroom might weigh one third of what it would have weighed 100 or more years ago. At the same time, my sleeping gear will keep me warm in a tent when the temperature is 50 degrees below zero Fahrenheit.

The Scott expedition 100 years ago in Antarctica had eider down sleeping bags available. Eider, the warmest down on the face of the planet, like goose down, begins to fail at the first hint of body moisture. The Scott expedition was unable to preserve the fill power from the body’s moisture. Therefore, when Scott made his successful attempt to arrive at the South Pole, he was compelled to use the much heavier fur and wool blankets for sleeping gear. While their blankets and furs held up far better than a down sleeping bag, eventually their sleeping system failed due to the moisture buildup from their bodies. During their return, the men, along with Scott, froze to death before getting back to safety. They died in their sleeping gear. The short of this is that the weight of the gear of 100 years ago slowed the Scott expedition down and made the trip far more dangerous, and as it turned out impossible. Today, we have the means to protect the extremely lightweight down. If that were not the case, then I would likely freeze to death sometime after the 7th day of the 90-day trip.

The conclusion of this is that there is nothing exceptional about us today. For that matter, physically the mountain men were undeniably far superior to us. However, with the equipment we possess today, it is possible for us to access locations where the mountain men were incapable of getting to, or even had any interest in “being the first”.