June 2015 Update

During the last two winters, my attempts to travel along the Continental Divide of Montana and Idaho have proven to be elusive. I am now convinced that for me to have any chance of completing the trip changes must happen.

Yes, I have heard the naysayers’ statements and endured a few lectures concerning the impossibility of the undertaking. I’m wondering though, when the words “challenge” and “easy” became synonymous.

With two winters of experience on the route, I am coming to understand why the trip has never been successfully undertaken. Everything about it including the logistic and physical preparations are daunting. Clearly, the trip’s challenges are more than holding their own with me. Frankly, I am getting my butt kicked, which, by the way is no good reason to quit, but remains a good reason to change what I am doing. Two alterations are in the works. They concern the food and certain areas of the route.

The winter load for an extended trip is huge. On a two to three night winter trip, one may get away with going into the backcountry with a lighter load. However, having less equipment on an expedition trip could prove fatal.

An example of this is the down sleeping bag. Each night of use, the body evaporates approximately one pint of water straight into the down, where it freezes near the surface and collapses the fill power of the natural material. Within one week, the sleeping bag approaches uselessness for retaining heat. Then along comes a subzero cold, placing the traveler in peril.

Many have died as the result of this condition. The Scott expedition to the South Pole killed Scott and his men because of the nightly retention of moisture, which eventually neutralized the heat retaining properties of their sleeping gear. To his credit, Scott recognized they would be unable to use the down sleeping bags because of this handicap. However, the much heavier furs and wool blankets, besides slowing their pace, also eventually failed. When Scott was located, he was in his tent and in his sleeping gear, having succumbed to the cold.

I carry a -20 Fahrenheit down sleeping bag. Before beginning the Continental Divide trip, I used a zero Fahrenheit rated sleeping bag. On numerous occasions after several nights of use, I have felt the chill inside the sleeping bag. At the beginning of a winter trip using this earlier sleeping system, I have been completely toasty regardless of the cold, only to feel the chill seeping into the bag after three or four nights. One such occasion occurred in Glacier National Park. On the seventh night of a trip, I almost lost my life, which was a result of this increasingly dangerous condition. Because most of the trips were so short though, seven days or less, through the years I continued to use this sleeping system, which included a light bivy sack, two pads, and occasional fleece blanket.

Regardless the length of the winter trip, the bedroom is the final bastion against the winter cold—when all else fails the bedroom must keep me safe. For this reason, the length of the Continental Divide trip, a long-term exposure to the cold, changed things. I was going to need a stronger bedroom setup.

Thus, I purchased a much warmer system, at a price though beyond the steep financial cost. In addition to the heavier sleeping bag and bivy sack, I also purchased a thicker pad and a vapor barrier liner. The latter item protected the down from my body moisture. My entire bedroom including the camp chair now weighed 10 pounds. The consequences came with a slower pace, enough to need more food and fuel for the extra days of travel, which increased the weight even more, whilst slowing me further. What I am describing is the snowball effect that affects all travelers regardless of the season or the length of the trip, and in particular the winter expedition trip.

As a result, my quandary of the last two winters is a too heavy load. Now entering the summer of 2015, I know very well that at 64 years old, time is short. I will find a way to lighten the load or give up the trip. The changes are already in motion.

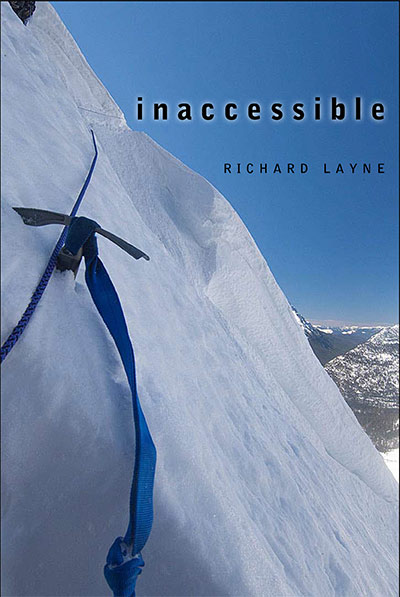

Out for the winter of 2015 and 2016 are my previous plans for an intentional challenge of areas requiring climbing gear along the route, which precipitates an immediate 13-pound drop in the load. At the most, on occasion I will carry the ice ax and crampons, a weight increase of 3.92 pounds. For the most part, my route is now more in line with the actual Continental Divide Trail.

There is also a change in the food I eat. I have already purchased over 500 freeze-dried meals. While the weight loss is not large, there is a substantial and necessary increase in the calories and protein, with the cooking time dramatically lessened. I will talk about this necessary increase shortly.

The dehydrated vegan stew, my main hot staple for the last nine years, takes approximately 44 minutes to boil and then simmer before being ready to eat. The water for the freeze-dried food takes three minutes to boil, and then turn the stove off, creating a huge drop in fuel needs by approximately 10 ounces per day. In addition to the jump in the palate, the freeze-dried food also increases the daily calories and protein by over 1100 calories and 70 grams respectively, while dropping the load by another seven ounces per day.

Before the change to freeze-dried food, my main fare lost its tastiness. In addition to this were the doubts my wife and I shared concerning the 6000 calories I was supposed to consume daily on the trips. If I traveled 4 hours using 1000 calories per hour, I would only have 2000 calories for the remaining 20 hours of the day. Because of my refusal to eat more than a small amount of the nourishment each day, if any at all, came the minimal backpack weight loss, along with the lack of being re-energized. Each day within the first hour of travel, I would be tired. For the remainder of the day I would struggle to make any distance whatsoever. While a great body weight loss program, this also figured large in the failure of my previous trips.

I have no doubt the freeze-dried food has remedied my eating problem in the backcountry. I base that off the last trip, which was seven days in length. I had six freeze-dried food packets, two per day, leaving me four days of eating my old fare. I consumed the freeze-dried food with relish, and then almost stopped eating for the remaining four days. Therefore, two things have happened because of freeze-dried food. I am finally eating the food that is with me and I will be consuming over 7300 calories per day next winter.

I would like to conclude this by saying that one week ago; I exited Henrys Lake Mountains with the climbing gear and snowshoes attached to the backpack. I weighed the entire load when I arrived back home. While the spreadsheet said the load should have weighed no more than 82 pounds, the actual weight was 85. Too damned much, I felt like I was carrying my own cross to the crucifixion.

As it stands right now having reduced my full load to approximately 70 pounds, I can live with that. With this altered load during the winter trip, on the day I arrive at each resupply I will be carrying 55 pounds, damn near angel’s wings.

With more alterations to the trip coming in the next several months, these two changes have already recharged my hope for completing the trip.