A Premature Trip

I left Lima Montana on December 2, 2018. While antsy to get going, I was also worried. The day before, I had driven through the snowpack 12.2 miles to Sawmill Creek trailhead without issue. Throughout the drive however, I had spotted gravel on the snow-covered road surface, something the sled would not be able to handle. On that same day in a day hike, I walked 1.3 miles and ascended nearly 900 feet up Sawmill Creek Ridgeline. Throughout the walk, I had encountered rocks, roots, and sagebrush. On December 2, another day hike was not forthcoming, but rather the Continental Divide trip itself would begin. Would there be enough snow?

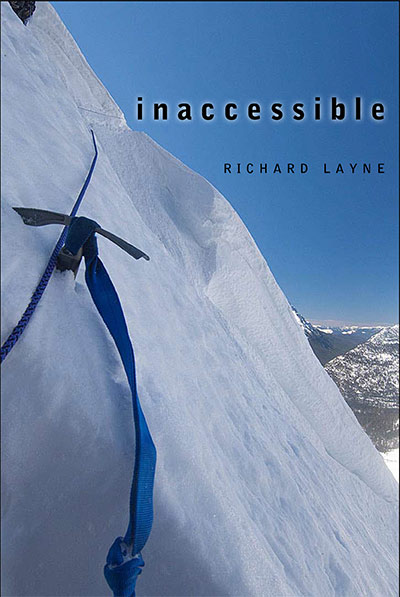

Caption for photo at top of the post: The Thumb (9,700 feet) located in the southernmost area of the Bitterroot Range, can be seen from Interstate Highway 15, 6 miles north of Monida Pass. The peak complex, shared by Montana and Idaho, is part of the Continental Divide.

At my second camp on the ridgeline, the snow remained not quite enough. I continued to hold out hope that as I ascended to the base of Red Conglomerate Peaks there would eventually be enough snow to protect the belly of my new sled. Arriving at the third camp, although the snow was deeper my sled had scraped over protruding rocks less than 100 feet from where I built my camp. The following morning, now near the saddle that would take me into Little Sheep Creek drainage, I knew that the snowpack was not going to get much deeper; I messaged my wife that I would exit. She arrived at the trailhead by midafternoon, and we headed home.

Long before December 1, I knew I would be taking a chance on whether there would be enough snow for the sled. What I had sought to do was to have enough powder snow to travel in, which was not yet deep enough to stop my forward progress. This type of snow is the norm until at least mid-February. Pushing through a foot and half to 3 feet of powder is extraordinarily difficult. For the backcountry traveler using either cross-country skis or snowshoes, powder snow is the bane of forward progress. With this in mind, I nevertheless sought to cut into the 220 miles of travel for the winter of 2019, although I quietly thought if I was somehow cheating. Only, because of the too low snowpack, I did not get away with this strategy. In the process, I might even have destroyed a new sled. Whether I will have to replace it remains undecided.

To be clear, I am not open to any sort of discourse on what I consider is cheating. What I believe is what I will go with in a summary of those six days on the ridgeline. As tempting as it remains to be, I will make no further attempts at traveling with a sled in a too low snowpack. What that interprets for the trip is a big wait of approximately 60 days until the snowpack has a base and a crust. In addition, it is doubtful I will forgo the sled and travel with only a backpack. Those days are likely at an end.

On the other hand, if I do go in with just a backpack and snowshoes my load weight will be approximately 70 pounds, which is the bare-bones survival level. An example of the peril this load would have trouble coping with would be if the temperature dropped to 40 degrees below zero Fahrenheit. If it stayed there for two or more days, I would be in trouble. Nevertheless, because I am anxious to travel I will give the backpack without a sled more consideration for this first leg of the journey.