(Click on any photo to enlarge.)

(Click on any photo to enlarge.)

Chapter 1: Rising to the Challenge

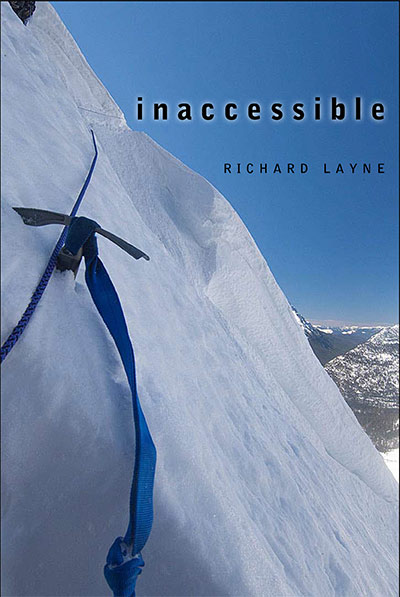

In the pre-dawn light on May 15, 2011, the swirling clouds lifted—and my heart sank. In the distance, my destination beckoned: Hole in the Wall, a large, snow-filled, bowl-shaped cirque rimmed by ragged, black peaks and saw-toothed arêtes. From where I stood—alone, beyond help, beyond reason, in front of my tent just west of Brown Pass—I knew that the gleaming, untracked snow of Hole in the Wall awaited, an oasis of gently rolling terrain in an otherwise near-vertical world. The distance from my camp to Hole in the Wall was a mere three-quarters of a mile. But I knew that those 4,000 feet were tilted 70 degrees or more, punctuated by cliffs, ravines, and avalanche debris. The snow there was deep and untested—poised to crack, primed to fail. The pit of my stomach went hollow with fear.

The only reason I was standing in this spot was to traverse the slope ahead and enter Hole in the Wall. During summer, hikers stroll here on a well-worn trail cut back into the steep angle of the mountains’ flanks, skirting cliffs and contouring easily into the cirque, then on to Boulder Pass and the Kintla Lakes drainage to the west. But May in Glacier’s high country is still winter. Seven months of accumulated snow rest uneasily on the mountains, temperatures dive well below freezing, and fast-moving storms dump more snow on the unstable slopes. Park rangers and managers had warned that Hole in the Wall was inaccessible during winter; no one had ever entered the cirque under winter conditions. No one was crazy enough to try. If the deep snow and miserable weather didn’t stop an intrepid backcountry traveler, surely the trackless plunge of the traverse from Brown Pass to Hole in the Wall would bring a person to his senses. The sheer slope offered no protection, no safe haven. In short, if you didn’t fall to your death, one of the frequent earth-shaking avalanches would surely finish the job.

But I needed to reach Hole in the Wall. If I hoped to succeed in my larger dream of crossing the entire length of Glacier National Park in the winter, I had to prove that this traverse was survivable. The death trap ahead was the keyhole that unlocked Glacier’s Livingstone Range and the northwestern end of the route across the park.

My timing could not have been much worse. During the winter of 2010-2011, a La Niña weather pattern hurled storm after moisture-laden storm at Glacier’s peaks. By May, the snowpack was 200 percent of average, and the forecast called for yet another train of low-pressure systems to dump more snow. Hole in the Wall’s reputation as unassailable seemed secure for at least another year. A sane person would have turned around. I gathered my gear and stepped forward.

Why take the risk? Why even contemplate such a trip in the first place, never mind the even crazier scheme of crossing the entirety of Glacier, alone, in the winter? A simple “Because it’s there” wouldn’t suffice. If the challenge before me was at all about this particular place, it was even more about a lifetime of rising to challenges, a lifetime of defying the odds as others saw them.

Apparently, this ambition started at an early age during my first year in Arkansas. Among my belongings is a black and white photograph of a baby boy, clearly less than a year old. He wears a white cloth diaper, nothing else. The infant stands midway on the stairs of a porch, either going up or coming down. On the back of the picture in my mother’s handwriting is the name “Richard.” This early climbing career was nearly cut short, however, by a bout of infectious colitis. Two neighbor children had died from the colitis, and my mother was caring for their ailing mother, which is likely how I caught the disease. I wasted away for six weeks, until finally, when I was 11 months old, we left Arkansas for Missoula, Montana, where my mother had been born and raised. During the long bus ride north, my mother fed me laudanum-laced sugar water to quiet me, so she could get some rest. When we arrived in Missoula, an aunt asked her doctor for a prescription that finally cleared the colitis. But I bear the scars to this day with a hernia that stretches from my sternum to my lower abdominal muscles. With a weakened immune system, getting grievously sick became a part of my life. In the coming years, I sometimes missed weeks of school.

Other forms of trouble, mostly self-induced, soon developed. Shortly after arriving in Montana, I nearly drowned in a milk bucket on my grandparent’s dairy farm, saved at the last moment by my mother. Not long after I followed my two older brothers to an irrigation ditch. Again, mom came to the rescue. Frantically searching in muddy water up to her neck, she somehow found me and yanked me to the surface. I have no conscious memory of any of these incidents. Yet to this day, I have trouble burying my face in a mummy sleeping bag or walking on ice-covered lakes.

The third of eight children, we grew up in a world of poverty surrounded by people with plenty in the Bitterroot Valley. In the late winter of 1960, we lived for one month without electricity; the only light came from candles my mother made from animal tallow. My youngest sibling was six months old when we moved again, this time without our father. By then we had already felt the hunger that went with an empty larder.

Our home for the next three and a half years was three miles from the nearest town. For the first time we knew enough stability to cease going hungry. Nearby pastures and farm fields held an ample supply of Chinese pheasants and an occasional jackrabbit, and local streams provided ducks and trout. We also had a large garden, and across the creek bordering the west side of our yard was a chicken coop that was restocked with 50 chicks and 16 poult turkeys every spring. We also had rabbits and pigs. Our outhouse, a two-seater, had doubled in size.

There was electricity, and eventually a black-and-white TV that sometimes worked. In the boys’ bedroom were two sets of bunk beds, one large bed, a boys’ community dresser, and a woodstove. The living room held another woodstove, and a third in the kitchen was both a cook stove and water heater. The water heater was almost large enough to get a shower, located in the girls’ room. We also finally connected to the rest of society with a telephone.

During that first summer without our father (who was soon enjoying free meals at the Montana State Penitentiary), my mother picked strawberries, raspberries, and blackberries for a farm one mile from our home. She took my two older brothers to help. My younger sister and I cared for our younger siblings, with the two youngest still in diapers. My mother’s income, supplemented by government welfare checks, also included medical assistance, a fact that soon became public information. Some of my classmates at school took that to mean we could afford the mental and physical punishment they then inflicted on me. By 1964, I felt like a lower class of human being, which created a smoldering, but growing fire within me.

In this rural setting, the two older brothers and two of the younger brothers teamed with each other as duos. I tried to tag along with the elder two, although often spurned as too young. Less often, I joined the younger two. Through the years however, I began to go out alone. Growing up in a rural mountainous setting, “going out” meant visiting the river bottom or hiking into the mountains. We lacked money for school activities or fun in town. Even when we eventually moved into the town of Hamilton, population approximately 3,000, our idea of fun usually took us outside city limits.

Throughout my adolescence, evidence mounted that years of illness and deprivation were taking their toll physically and mentally. In 1965, faced with the prospect of a second try at seventh grade I went into a tailspin. Since I had also repeated the first grade, I was two years older than my classmates, although physically smaller than many of them. My new classmates also included a younger sister. Regardless of my efforts, it seemed I would always fall short. Unwilling to fully resign myself to this fate, I resisted. Unfortunately, the harder I fought, the worse my situation became. My fear of others grew, particularly when they were in groups. For relief, increasingly I wandered the nearby canyons and mountains alone.

If 1965 was a bleak year for me, it also brought a special opportunity—a one-week backcountry trip with the Boy Scout troop from Corvallis, a small town north of Hamilton. I lacked the gear the other boys had, and I suffered during the long, cold nights, but I secretly swooned over the experience. I now had a dream: to spend more time traveling in the backcountry. All I had to do was get some of the gear the others possessed—boots, backpack, tent, cookware, and sleeping bag.

A childhood of hardships had taught me how to live with what little was immediately available. We couldn’t afford winter gloves or mittens, so I made do with old socks. A heavy coat was an impossible luxury, so I learned to dress in layers. I found that dead grass stuffed into my shoes could soak up water when a foot went into the creek. Cattails and haystacks offered insulation against the cold. For overnight trips, my kitchen was a cast-iron skillet, which sometimes dug into my back, while my larder consisted of flour or cornmeal, salt, pepper, russet potatoes, and sometimes bacon. Fishing gear gave the promise of protein. Although I was deeply embarrassed by these make-shift provisions at the time, they became a great asset in later years, a wellspring of self reliance and assurance in adverse conditions. When taxed to the limit, these life lessons would more than once save my life.

In 1969, two months short of my 18th birthday, I dropped out of high school and abruptly decided to leave town. The U.S. Army offered a way out. The recruiter assured me that if I signed a three-year contract, the Army would train me as a helicopter crew chief. If they fell through on this promise, I could get them on a breach of contract and receive a discharge.

Beyond my very small sphere of attention, I was vaguely aware of the protests and civil unrest against the enormously unpopular Vietnam War. Young men were burning their draft cards, enrolling and loitering in college, and even hiding in Canada—anything to escape the military draft. From where I stood, they looked desperate to avoid a step down into what looked like a step up for me. Over the radio, I listened to a young woman belt out a goodbye song, a country-western singer question Suzy about where the playground was located, and another crooner complaining about one being the loneliest number, which was something I had known for too long. Mostly though, time was tight and I was desperate to get the hell out of a world with no hope.

“And when would you like to leave?,” the recruiter asked. “As soon as possible? Is five days too long to wait? It is, but okay?”

When I entered Army basic training, I weighed 155 pounds and my height at five feet nine inches was as tall as I would ever get. For the next two months, the drill instructors pummeled 150 of us through physical exercise and not enough to eat. On average, most trainees lost weight, some upwards of 40 pounds. I, on the other hand, gained 10 pounds.

The recruiter and the Army held up their end of the contract, even after I decided it was no longer necessary. While I was going through helicopter mechanic training in Alabama, I discovered that the Army was paying already active soldiers to re-enlist for six years as helicopter crew chiefs, with a re-enlistment payout of $10,000. At the time, that was the highest re-enlistment bonus, reserved for critical jobs. By all that I could see, the only thing critical about the helicopter crew chief was there were not enough people signing up. I came cheap. The Army got me for three years with an initial paycheck of $96 per month.

Five months and eight days after enlisting, I arrived in Vietnam. While waiting at the Long Binh Army base a few days later for permanent assignment, an Army officer asked if any of the several hundred of us would like to volunteer for long-range patrol or Special Forces duty. No one stood up; I too stayed seated. Still feeling like I was on the edge of nothing, my inaction left me feeling soiled. That would be the last time I would say no to avoid combat. Nothing I did, however, eased the load of baggage that came with me when I entered the Army.

In another month, I was beginning to adjust to a monsoon season and copious quantities of red mud several miles south of the De-Militarized Zone, when I volunteered for permanent perimeter guard duty. Eighteen months later, I could look back on surviving several crises, including riding a destroyed helicopter to the ground and a short visit to Laos, where a day earlier enemy gunfire downed one of our helicopters.

In July 1970, I was nine months inside Vietnam when the Army gave me a 30-day leave. I flew home to Montana. On my return, I brought back pictures and showed them to the small group of my buddies. When we got to the photos of a couple friends and I prepared to go backpacking, my buddies couldn’t hide their surprise, which in turn embarrassed me. Leave was supposed to be spent pursuing women, letting your hair grow, and drinking. The thought of leaving the war zone for 30 days and spending any of it in the backcountry seemed ridiculous. In Vietnam, the men often talked about life back home—the women, the food, and amenities we had taken for granted. There was never any talk, however, about hiking into the backcountry. My buddies yearned to get back to civilization; that sounded good to me, too, but I also craved wilderness. Despite the dangers, I often sought solace during the daytime alone at the bunker, along perimeter, and sometimes further afield.

Always one to buck the norm, I volunteered for an extra six months in Vietnam. As I prepared to put in for a second six-month extension, the Army said no. On that terrible day in April 1971, one month before I was due to leave Vietnam, the unit’s captain saw the rejection written across my 19-year-old face. He put a hand on one of my shoulders, and in a soft voice said, “Someday you will thank me for this, Layne.” Sixty days earlier, he had shown nothing but anger and disdain for me. If I was already easy to dislike, my disgusting drinking bouts further drove people away. After the destruction of my helicopter, I arrived as a volunteer at our temporary forward base on the dangerous Khe Sanh plateau located in the northwest corner of South Vietnam. With no alcohol available up there, my sober but abnormally risky actions soon changed the captain’s opinion of me. Now back at our rear area, he probably thought he had just saved my life. It also re-validated that the captain’s opinion of me had gone through a revision while we were at Khe Sanh, in spite of my resumed drinking once we returned to our rear base.

That backpacking trip in 1970 was the last one for 13 years. In July 1983, I was now divorced with three children. Although unaware of it at the time, I was in the last week of a 15-year drinking binge. No longer employable, I was homeless except for my tolerant but reluctant family members. I asked a brother-in-law to loan me some backpacking gear, a .357 revolver, and several boxes of bullets. Then I attempted to get sane and sober in the one place that had been my comforter since I was a teenager, the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness. My plan was to return to civilization only for re-supplies for the remainder of my life. Failing at that, perhaps I would be able to use the pistol to remove the horror that was my life.

Alcoholism is a powerful illness. The mountains did not betray me, but only partly relieved the pain. The first two days I traveled to the end of one canyon and climbed the wall into the next. I woke up dry and comfortable, but to a steady rainfall. The drizzle gave me the excuse I wanted, and I declared I had to get the hell out of there. Five hours and two inadvisable creek crossings later, I sat in a bar near Stevensville with a drink in my hand, suffering from a mild case of hypothermia.

I gradually pulled my life together. In July 1993, remarried, I accompanied my wife Carleen, a native Montanan, on her first-ever trip into the backcountry. We entered Idaho’s Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness for a four-day trip. To make her as comfortable as possible, I borrowed a lightweight tent. I also purchased two closed-cell sleeping pads, lightweight kitchen gear, cheap but genuine hiking boots, ponchos, and two (until then unheard-of) internal frame backpacks. This was far more than I had ever taken into the backcountry. For all of that, at the end of each miserable day Carleen was comfortable and warm inside the tent. Meanwhile I had just re-discovered the security of the mountains and a way to travel in them year-round. In spite of nonstop rain (except when it was snowing), a sprained ankle, and extensive off-trail travel in the jungle of fallen timber, she loved the experience.

During the ensuing years, Carleen and I went on trips of up to two weeks duration in all four seasons. She took to the backcountry like an old hand. Learning quickly, soon she could read a map and compass and was at ease traveling off-trail deep into the wilderness. She also learned to locate water in seemingly dry areas. In August 1999, I thought I lost Carleen when, in a solo test, I sent her through trees and heavy brush in a specific direction for water, using a compass for navigation. She re-appeared an hour later bubbling with excitement, having successfully navigated alone and found the water. Her enthusiasm almost removed the “scared to death” lump lodged in my throat. Shortly after that, we began to carry two-way radios.

In December 1993, with ongoing equipment improvements and additions, Carleen and I began taking more serious winter trips. But in 1996, a particularly hazardous trip into the deep snows of the Selway-Bitterroot made us reconsider the risks. Thereafter, our winter trips together were restricted to the lower elevations of the Selway River canyon on the western side of the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness, where we repeatedly saw buttercups blooming near the end of January.

Camping gear had changed drastically since I was a teenager. With the stronger and lighter gear came the sense of being able to travel in the most remote areas I could find, and in the worst sort of weather. No matter how bad the day or extreme the environment, I felt that inside the tent was comfort, food, warmth, and security. (Soon enough the outside conditions would permeate the interior of my tent and almost take my life, while removing any residue sense of invulnerability.)

Through the years, the trips grew more difficult until finally I approached a magazine editor with the idea of crossing the Bob Marshall Wilderness in winter and then writing about it. I was unable to say no when she suggested instead that I attempt a winter crossing of Glacier National Park. With multiple years of winter travel inside the Selway-Bitterroot, Bob Marshall, and Scapegoat Wildernesses, I thought that if it was at all possible to make the crossing, I might be the one to do it. I started making winter reconnaissance trips into Glacier, using an ice axe and crampons for the first time. Ultimately, I found myself perched just below the Continental Divide at Ahern Pass staring at an impossible route forward and unable to retreat. I survived what would have been a lethal fall with a well-placed ice axe and then a long night in a tent listening to avalanches roar all around, waiting to be crushed and swept away by the enormous cornice hanging above my campsite. Horrified at the precarious circumstances and utterly exhausted, I swore that if I survived the trip I would never do such a trip again.

Through sheer stubbornness, I did survive, crossing Ahern Pass against all odds. As I drove homeward, I made a phone call to my spiritual advisor of 18 years, who resided in Los Angeles. With a growl, he said, “Well, I hope you got that out of your system.” As soon as I heard those words, I realized that I had spoken too soon in my despair below the cornice on Ahern. Like a thirsty man whose lips had just touched cool sweet water, I was already yearning for more.

Originally, I sought the backcountry for relief from my fear of people. Now the challenge of staying alive while trekking where few or none have ventured has trumped that reason. Moreover, it is almost impossible to experience quiet solace on the side of a mountain while fearing the next snowpack-shaking avalanche. In the nearly two decades since I returned to the backcountry, old age is nipping at me. The prospect of never again getting to stand atop Ahern or Blodgett Pass in a howling blizzard is in sight. To me that thought is awful, so I continue to resist the inevitable.

Which is how I came to be on the doorstep of Hole in the Wall.