Tent or Snow Cave

When discussing backcountry winter travel, it is almost inevitable that someone will ask if I stay in a snow cave at the end of each day. That train of thought is understandable. When a person with little or no experience tries to comprehend surviving in the sometimes-bitter cold, particularly in a camp, this is one of the attempts to wrap one’s head around living in the extreme environment. In light of the occasional news story of someone who survived a harrowing winter experience only because of a snow cave, it seems like a natural question. Nor am I going to give the “real story” demonstrating the fallacies of such stories. In my experience, the cave is vastly superior to the tent for protection against the outside environment. The difference of having two thin layers of material separating the outside conditions from me as opposed to half a foot or more of snowpack, but for the serious nature of the environment, is almost laughable.

That being the case, then why use a tent at all? The answer is simple enough. Regardless of my strength and endurance while traveling in a winter setting, by the time I arrive at my next camp location I am exhausted. Where a group of travelers is concerned, outside of the greater distance traveled I doubt that they would fare any better. Here’s why, while traveling alone with a load of 80 and more pounds through a January powder snowpack, a measly three miles in a single day is almost a noteworthy day. Meanwhile in the same conditions a group of three or more travelers will travel nine or more miles. Either way, at the end of each day both parties are going to be tired.

Building a snow cave is not something one slaps together in an hour or two, nor is the labor eased by being among a group of travelers. The cave has to be big enough to handle everyone just as my much smaller one-man cave only has to be large enough to handle me. Regardless of the number of people in the party, three to five hours of work are involved in building a snow cave.

To a lesser degree, there are other reasons that works against building a cave at the end of each day of travel. For starters, when the sun disappears behind the western mountains, within minutes the temperature can drop by 5°F to 10°F. In addition, during the winter the days are much shorter. After traveling five hours in a single day, which incidentally equates out to at least 5000 consumed calories, beyond the exhaustion is also the amount of daylight remaining to build a camp. Much can be said for building a camp while it is still light. Equipment losses in the darkness need to be a consideration. Although I rarely lose equipment, summer or winter, it can happen. Far less forgiving than summer, the loss of equipment during the winter can actually be life threatening. Therefore, for safety’s sake, it is prudent to set up camp before darkness sets in.

While it takes at least three hours to dig a snow cave, a properly prepared camp with a tent takes approximately one hour to build. This includes piling snow around the edges of the tent, setting most if not all of the anchor ropes, retrieving water where possible and a host of other chores before finally crawling into the tent. Many of these chores are not just exclusive to building a camp with a tent. (Please spare me the details of how there is no open or running water during the winter. There are a host of generally accepted facts that fail to coincide with my experience in the backcountry, such as grizzlies staying in their dens throughout the winter months.)

In short, after an exhaustive day of travel there is very little daylight remaining for the several hours of digging out a cave. That means I use the tent while traveling, including while hunkered down in normal bad weather.

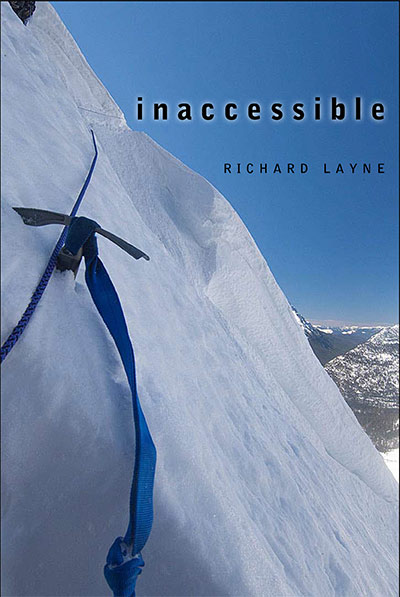

There are circumstances however, where it is vital to utilize a snow cave rather than a tent. On one trip, caught on the side of a mountain during a storm I had no alternative but to build a cave. It made no difference that the entire mountainside was an avalanche chute. I could go no further nor could I back out. The time was noon and I had been on the treeless slab for 24 hours.

In the latter afternoon of the previous day, I had dug a flat large enough for the tent shell to cover the camp. The storm arrived that night. By the middle of the following day there was near continuous spindrift. In addition, there was the possibility of avalanches. To only have built a flat for the tent would have been too dangerous. For that matter, the 60-degree slope I was located on left me without any assurance that the snow cave would have protected me in the event of a large avalanche. Nevertheless, it would have afforded me greater protection than the tent. Even with a small avalanche, I have little doubt what the outcome would have been inside the tent.

I had to build a second snow cave 48 hours later. Thirty minutes after entering this cave a roaring and tumultuous cave-shaking avalanche passed by less than 20 feet from the cave entrance. During the 36-hour period I was located in this cave, chunks of ice, snowpack, and rocks sporadically dropped on my position. If I somehow had evaded them, the flying missiles still would have destroyed the tent long before I moved on.

So yes, there are occasions when a snow cave is essential to survival, but mostly not.