While the snowpack on the Continental Divide in the Bitterroot Range of Montana and Idaho remains soft, change is in the works. With the more direct rays of the mid-March sun coupled with a forecast in the next seven days of warming temperatures, a crust is finally going to form on the surface. That means I will be able to travel with lessening danger of breaking through the surface of the snow.

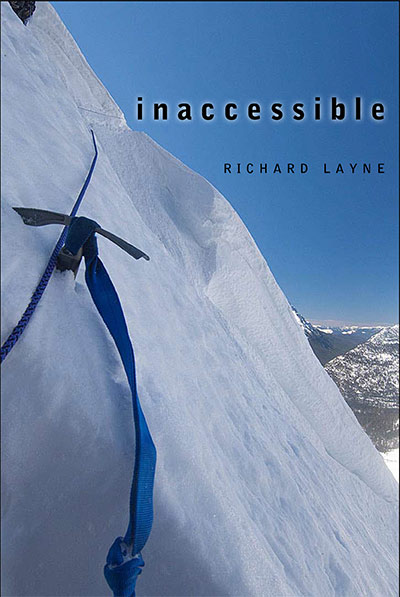

Because I travel alone during the winter, conservative actions are essential. That means I should take no chances in the many feet of deep snowpack with anything less than a strong crust. The snowpack needs to carry my weight and a large backpack, in addition to pulling a sled. While wearing snowshoes, a deep plunge through the snow with a load can blowout joints and even break bones. An accident like this can happen even on a flat, but is particularly hazardous in a descent. In addition, if the crust is just barely strong enough to carry my weight, that is synonymous to more plunging in an ascent, making the climb impossible to complete without breaking the load down and ferrying my gear and supplies to the top of the hill/mountain. Need I say that there is no joy in that type of travel?

Powder snow or a weak crust is tough to travel through, impossible on a long haul, and nearly so when only going out for two or three days. In the next 60 days, I plan to exit three times for two days each over a distance of 203 miles. The rest of the time, I will be ascending and descending continuously, doing push back on the cold while evading the Continental Divide’s windy storms and the consequential avalanche zones. The last thing I need is to go out on a snowpack that will not hold approximately 300 pounds of weight.