Every season in every year has its own flavor, and though still early, 2019’s autumn is no exception. About one week after the official arrival of autumn in September there came an early winter storm. In my own backyard located in Helena Montana, the storm dropped eight inches of snow. No record, but eventful. Knowing the forecast, in an overnight trip before the weather arrived I hurriedly drove to an area on the Continental Divide and placed four resupplies for this upcoming winter’s trip. I was back home 48 hours before the storm dropped in on us.

I waited one week before I resumed placing more resupplies. On October 5, the day I left I got one final forecast. I knew that a small and quick weather front that contained a mixture of rain and snow was coming Tuesday evening and Wednesday, replaced by sunshine and warming temperatures by Thursday. Despite the mud, I figured that I would be able to ride out this storm on the Divide while it passed through. I was wrong. On Monday, Carleen sent a message informing me of the drastic change in the forecast. The pervading thought was that perhaps I had better drop to a lower altitude. As a result, on the third night I stayed in Lima at the Mountain View Motel’s RV campground. The next day showed a forecast with much more deterioration of the weather. That is when I decided to ride out the storm in the TV room at home. As it turned out, my latest revised plan was a good one. We got another eight inches of snow in the backyard, this time with single digit temperatures. At some locations in our state, the temperatures dropped below 0°F.

While I am set up to handle a storm of this magnitude in the backcountry, my head was nowhere near ready. Not after what happened during the second trip on Saturday and Sunday, and to a lesser degree, Monday.

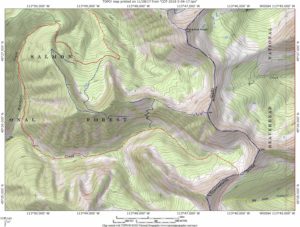

My plan for placing the resupplies during the second trip was to begin at the most remote location of next winter’s route, which was near the south side of Elk Mountain 10 miles north of Morrison Lake in Southwest Montana. Shortly before arriving on the Continental Divide, I left the mud behind, replaced by snowpack from the first storm. The almost treeless rolling hills were numerous. There were 13 of them, most with a snowdrift near the bottom of each north face. Because I was going downhill each time I encountered these wind driven piles of snow, I readily blasted through them with my camper equipped four-wheel drive pickup. I suppose I was fortunate though. The largest descent, approximately 600 feet had a rather small snowdrift, easily gotten through. Unfortunately, the tires lost their grip off and on throughout the descent.

Each north face brought increasing worry. This route was also my exit, and the crosswind that created the snowdrifts in the first place continued unabated.

In the early evening, I had been busting through the snowdrifts for approximately one hour when I arrived on a small rise, which signified the area of the headwaters of Hildreth Creek. Although I had arrived at the location where I would be setting up camp for the night and placing the resupply, I nervously noted the strength of the westerly wind as it buffeted the truck. Staying with the plan, which had me spending the night in this area, I nevertheless relocated the vehicle to a less vulnerable location.

Retracing my tracks 500 feet south, I found a level location in the saddle below the first north face I would encounter during the exit. It occurred to me that I ought to place the resupply and exit that evening rather than waiting until the following morning. Not wanting to travel in this stuff during the hours of darkness, I decided against the evening exit.

Throughout the night, the wind shook the camper. The following morning however, I woke to a calm and blue-sky day. The temperature was nothing to write home about though, 17°F, the coldest I had experienced since the end of April. I broke camp before placing the resupply. I also continued to worry. Although it did not snow at all the night before, the wind had damaged the trail I created getting in to this location. I wondered if it was more than the vehicle would be able to handle during the exit. Less than 200 feet from me, yesterday’s tracks briefly disappeared in a fresh snowdrift at the bottom of the north face.

Once I started to drive, I got my answer within 20 minutes. The first two hills were approximately 75 feet high. My tires did some spinning out and the vehicle weaved about, but I got through those snowdrifts without issue. The third hill, much larger than the first two, but smaller than what was ahead, a mere 150 feet high, it had the largest snowdrift yet that morning. I got a 200-foot running start and at 10 or 15 mph smashed into the snowdrift, driving another 15 or 20 feet before I hit the brakes as I was coming to a stop. At this point, I could only hope I still had enough traction to back out the now high centered pickup.

Successful, and once again 200 feet away from the snowdrift, I hit the throttle, and once more slammed into the snowdrift, this time pushing ahead less than 6 feet beyond my last effort before again braking. Now queasy with fear, I stared at the snowdrift in front of me. I had barely made a dent in it, with the worst still in front of me. I was acutely aware that there were 10 more snowdrifts beyond this hill, many of far greater length and depth. Once again, I reversed the vehicle and was able to back out of the drift and down to the flat. It was now time to give my situation some more thought.

I’m figuring that some of you who are reading this, at this point are probably wondering what I thought I was doing. Yeah, I beat you to it. Because that is exactly what I was thinking in the saddle at the bottom of that hill. I was now regretting I had not exited the evening before, darkness be damned. More so, why did I have to come so far? I would have made out just fine next winter if I had placed the Hildreth resupply four or five miles south of here.

I thought about the equipment I carried in the pickup, designed to get me out of hard spots. The High Lift Jack, capable of handling 7000 pounds, part of a system of chains and heavy cable for getting the truck unstuck. Unfortunately, that system requires an anchor less than 100 feet distance such as a large tree or a 1000-pound boulder. There were no large rocks along this 10-mile distance, and most of the trees did not exist on the north face slopes. That meant if I got stuck all I had was the shovel. Doable I suppose, eventually. Nor were the four sets of chains for my tires going to be much good with a high centered vehicle.

There was another possible option though, one that I did not like. Back on the small rise 500 feet north of the previous night’s camp was a jeep trail that dropped off the ridgeline to the east into the Hildreth Creek drainage. I had known about it for years on my topographic map. It was one of my emergency exit routes off the Divide during the winter trip, which would take me down to the main road. Although unmaintained during the winter, Medicine Lodge Road was four miles east of the rise, and then another four miles north to where it was maintained throughout the year. That morning as I placed the resupply in a tree I had noticed the trail several hundred feet below my location. Had the sun heated up that part of the snowless south face ridge, enough to turn a frozen ground into a muddy uncontrollable slide? I certainly was not anxious to go find out, but my options had just faded in that unpenetrated snowdrift. I turned north.

Less than three quarters of a mile distance, I once again stopped the pickup. Shaken by my carelessness over the last day and now feeling mighty careful, I got out of the vehicle and made some posthole tracks over to the edge of the initial drop to get a more certain look at what I was proposing to descend. It looked doable, for more than just going down, but also for a possible return if needed. A quarter mile below the rise, I arrived at a saddle and making a right turn, began the south face descent. No longer in the snow, the steep face looked more dry than frozen. My confidence rose rapidly as I made my way down the jeep trail, sagebrush on either side of me. Oh yeah, I’ve got this.

Several minutes later, as I neared the Hildreth Creek draw the angle of descent was lessening when I spotted the left curve ahead. In addition, now came the shadow creating trees, with the consequential patches of snow, ice and mud. Moments later the front tires arrived on the mud, and the truck took on a mind of its own, sliding the front end off the trail to the left, immediately threatening to roll the truck on its right side. With my heart lodged in my throat, I spun the steering wheel to the right while simultaneously hitting the throttle. The spinning tires spewed mud all over the place. Several seconds later, all four tires were back in the deep grooves of the muddy jeep trail. Inside the next mile, I spun out a few more times, but not nearly as badly as the first incident.

After crossing Hildreth Creek, a short time later, I arrived at a tributary of Morrison Creek. Figuring I was finally safe, I stopped and gave my shaky legs a small stretch. Looking back at where I had been 40 minutes before, I decided I didn’t like that trail. Credit was due though. The trail may have saved my dog and I on October 6.

By the end of the day, in spite of more mud and snowpack, I got another resupply placed and was in position to place a third from my latest camp near Deadman Lake. On Monday, I placed three more resupplies and then exited the mountains.

In another few days, I am leaving again, and I have a confession to make. I have a strong desire that for the remaining resupply placement there will be nothing further to write.